Mother Oak ....more than meets the leaf.

Share

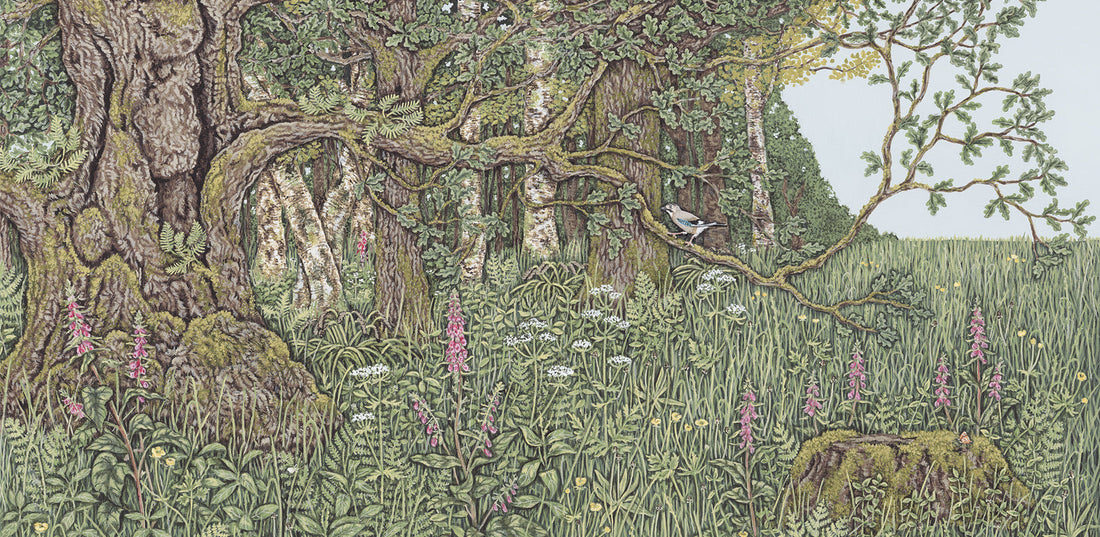

The English oaks (Quercus robur and Quercus petraea) are woven into the fabric of our landscape and cherished by many. They stand not only as trees, but as symbols of home, continuity, and belonging. Rooted deep in our history and culture, they embody a presence that many of us feel profoundly connected to. For years I have longed to capture their richness in detail, and Mother Oak is the culmination of three months’ work, the first step in an ongoing project exploring oaks and their multi-layered ecosystems.

Epitomes of reciprocity and diversity, our native oaks support more life than any other tree species in the UK, significant numbers of mammals, birds, insects, mosses, bryophytes, lichens, fungi, and microorganisms. Around 2,300 species are associated with them: 325 rely on oak entirely, and a further 229 are found rarely elsewhere1. Oaks offer shelter, structure, and food in abundance; even their deadwood is alive with possibility, harbouring some 700 species1. Many of these are bacteria and fungi, invisible to the human eye, yet play a vital role in woodland ecosystems. They are the decomposers and recyclers, forming the base of the food web, the exchangers of resources, and networks of communication2, 3 (often referred to as the wood wide web). The oldest known oak in Britain, thought to be the Bowthorpe Oak of Lincolnshire, is believed to have stood for a thousand years. Such veteran trees sustain far greater diversity than younger growth. They act as ‘hub’ trees, sharing these nutrients and resources with their offspring, and even with other species through the intricate underground mycorrhizal networks. This is why mixed communities are more resilient, each tree brings its own survival strategies. Older giants endure the flames of forest fires, where saplings perish. Break those networks, and their strength falters; fragmented communities are far less able to withstand disease or change4.

When I started work on Mother Oak I began only with the form of the veteran tree and the loose composition of its community. Usually I plan every last element meticulously, as I am always drawn to the detail, but this piece unfolded differently. So from there I started, and slowly the work began to flow. I have never taken so long over a single piece, and at times, my commercial artist head felt uncomfortable with the pace, wanting me to finish and make it efficient; but something in me told me to keep going, that this process felt right, and that it was leading me somewhere I needed to go. I started to feel a deep sense of peace when I was painting the oak, the same peace I feel whenever I’m physically around them, and I know I’m not alone in that. I had many conversations with visitors to the studio while I was painting, and without exception whenever I mentioned being in the presence of ancient oaks, a wistful expression would appear, normally accompanied by a sigh. In time my process became rooted in nature itself, the detail of the bark, branches, and understory reflecting the complexity of ecosystems. The parallels were inescapable: each element contributing to a greater whole.

Just as trees flourish in community, so too has my work been nurtured by the community around me. The past seven months working amidst my creative community have given me the time, space, and courage to follow what feels authentic, even when there is no guarantee of financial return. Ideally there is a balance to be struck, and most creatives know that familiar tension between working for pay and for passion, to walk the latter path requires resilience and commitment, but it becomes lighter when shared. In the conversations during the working day, I have found unexpected grounding in a phrase that resonated, and perspective or understanding that reframed and shifted something inside. These fragments take root in their own time and gently create direction. I know that had I been working in isolation, both myself and my work would be in a very different place. Is this path easier? No, but perhaps it is not meant to be. It is in the friction and tension, that something new can emerge. That is the gift of community, the foundation that allows us, like the forest, not just to survive but to thrive.

As so often happens when we look closely at nature, we find ourselves reflected there. The oak reminds us that we are rooted in this earth not separate to it, and just as woodlands thrive through diversity, so too do we. Our bodies depend on a varied biome to stay healthy, and our human communities need a diversity of voices, ideas, and beliefs to flourish. Without it, we risk division and brittleness, seen in the polarisation we witness daily on the world stage. We need community in all its forms: to share burdens in times of struggle, to navigate uncertainty, to celebrate, create, and come together.

As a painting Mother Oak is a portrait of relationship. A celebration of the oak’s generosity, of the ecosystems woven around it, and of the human parallels that echo through our own communities. As I painted, I found myself contemplating what woodlands embody: that resilience is born of diversity, that wisdom flows through networks, and that longevity comes not from standing alone, but from standing together. This piece marks only a beginning. My intention is to continue exploring the many ways oaks are rooted, and root us, in the land. Each veteran tree carries centuries within its bark, each community of trees tells a story of resilience and reciprocity. To walk among them is to be reminded that we too are threads in a living tapestry, sustained by the connections we weave with each other. Ecosystems are complex and messy, much like human beings. We may never fully understand our beautiful and ever-changing environment, but ongoing learning and acceptance of our impact on, and place in it is, I feel, key for their and therefore our ability to survive and thrive. Mother Oak is an invitation to look more closely at the life teeming around our ancient trees, and also to reflect on our own networks of belonging. Like the oak, may we find strength in our roots, generosity in our branches, and wisdom in the communities that hold us.

Further reading for oak and tree wisdom, all brilliant books from ecological, cultural, historical, and spiritual perspectives.

Being An Oak - Laurent Tillon.

Finding the Mother Tree - Suzanne Simard.

The Hidden Life of Trees - Peter Wohlleben.

The Lost Rainforests of Britain - Guy Shrubsole.

The Oak Papers - James Canton.

Woodlands - Oliver Rackham. I use this as more of a woodland bible to dip in and out of, an incredible mine of information.

1 Broome, A., Stokes, V., Mitchell, R. J., & Duncan, R. (2021). Ecological implications of oak decline in Great Britain. Forest Research, Research Note FRRN040.

2 Gorzelak, M.A., Asay, A.K., Pickles, B.J., Simard, S.W. (2015). Inter-plant communication through mycorrhizal networks mediates complex adaptive behaviour in plant communities. AoB PLANTS 7: plv050; doi:10.1093/aobpla/plv050

3 Wohlleben, P. (2017). The hidden life of trees. What they feel, how they communicate. Discoveries from a secret world. William Collins (UK paperback edition).

4 Simard, S. (2021). Finding the mother tree: Uncovering the wisdom and intelligence of the forest. Penguin UK.